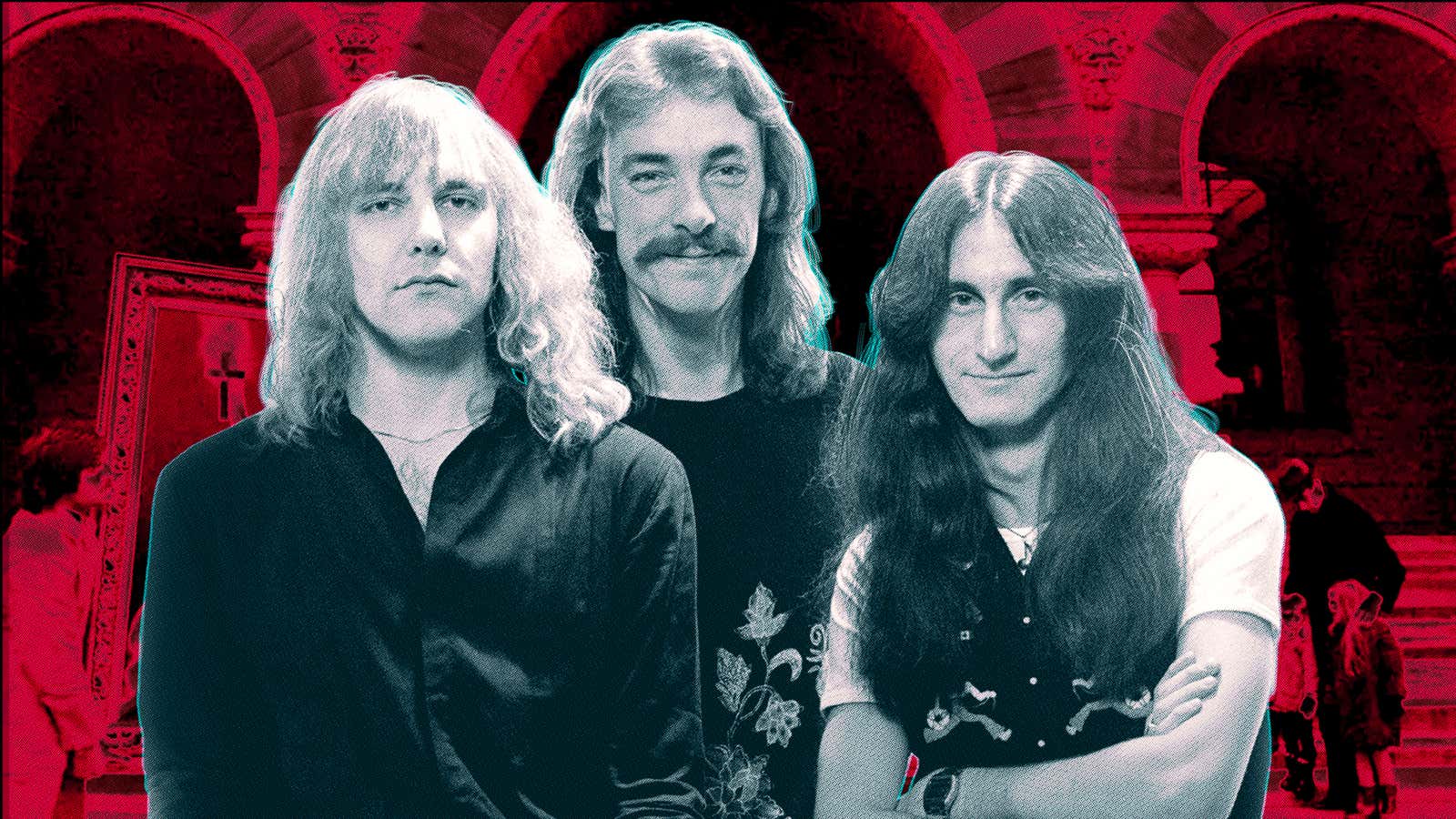

What’s the best Rush album? It’s the kind of question that can set off hours of debate among fans of Canada’s finest power trio, and with good reason: The band’s 19 studio albums contain a panoply of different styles and sounds, from the proggiest of finger-tenting, glasses-pushing-up prog-rock to the slickest of pop stylings.

So maybe a better question is: Which version of Rush is your favorite? Peruse just about any poll or ranking of its greatest records, and you’ll find a general consensus of sorts coming down to a handful of Rush albums; yet each one of these is a notably different-sounding band.

For starters, there’s the cosmic prog-metal of concept album 2112, the early release that was both the band’s commercial breakthrough and the out-there epic of sci-fi Objectivist philosophy that bought the band its subsequent creative independence. Or take Hemispheres, which reworked 2112’s more metal-tinged tendencies into a similarly outsized conceptual framework but paired it with some of the most playfully hard-rock experiments (“The Trees,” “La Villa Strangiato”) of the band’s career.

Prefer the synthesizers? Power Windows incorporates them seamlessly into an album full of the band’s least prog and most spacious songwriting. Arguably most surprising is the final album, Clockwork Angels, a hard-charging masterwork of rock and metal grooves that comes full circle back to 2112’s concept-album sci-fi milieu with its steampunk opera narrative. And of course, there’s Roll The Bones if you want to, uh, hear Geddy Lee rap. Just kidding: That underrated record makes for an ideal middle ground between Rush’s synth-heavy ’80s material and its subsequent return to power-trio hard rock.

But by just about any metric, 1981’s Moving Pictures remains one of the strongest contenders for Rush’s greatest work. It’s not just because it remains the band’s most commercially successful release, with 75 weeks spent on the Billboard charts and having been certified platinum five times over. It’s not just because it contains the song that will likely forever remain the band’s most culturally influential and enduring track, “Tom Sawyer.” And it’s not just because of the delightfully silly triple-entendre of the album cover.

It’s because of the music. These seven songs represent, maybe better than any other record the band released, the breadth and scope of which they were capable, from the tightest of pop-rock songwriting to the most expansive of complex, soaring arrangements to the most forward-thinking genre-blending of sounds that bridged the gap between the hard rock ’70s and new wave ’80s. And, as a new deluxe reissue for its 40th anniversary reminds listeners, the album displays—quite simply—a band at the height of its ass-kicking prowess.

Moving Pictures 40: A testament to innovation

If 2112 was the album that introduced the world at large to Rush’s outsized musical ambitions, 1978’s Hemispheres was the record that broke the band’s prog-epics back. Full of material so difficult to actually perform that, in some instances (the notoriously challenging “La Villa Strangiato”), efforts to record the whole song in an unbroken take proved impossible, it left the group feeling as though each of them had taken their dreams of musical overachievement as far as could be carried.

As a result, the next album, Permanent Waves, saw the beginning of a transition away from such dense, challenging material. Songs like “Freewill” and “The Spirit Of Radio” hinted not only at the more airwaves-friendly, accessible path ahead, but also contained hints of the melange of influences the band was steadily integrating, most notably reggae. But it was still early in that transition: Side one ended with the nearly eight-minute “Jacob’s Ladder,” and side two concludes on “Natural Science,” a nine-minute, three-part odyssey of shifting rock soundscapes. Meet The Beatles, this was not.

Moving Pictures, then, became the sweet spot where the band’s former penchant for behemoths of arrangement met a newfound appreciation for the knack of the well-turned hook, rendered clearly and with minimal lily-gilding. Or, as drummer Neil Peart explained in the 2010 Rush documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage, “That’s when we became us. Rush was born with Moving Pictures, really.” The hard-rock maestros had become something else, other and apart from the can-you-top-this bombasity of its prog-metal past.

You can hear it from the iconic opening chords of “Tom Sawyer” and “Limelight,” both of which embraced the new pop direction of Permanent Waves and refined it into a hook-meets-hard-edged composition. It’s there in the strummy melodies of “Red Barchetta,” starting off like a genteel pop groove before launching into a heady synthesis of fuming riffs and near-shoegaze levels of instrumental expansiveness. It’s impossible to miss in the elliptical, reggae-meets-power-pop thrum of “Vital Signs.” Even “The Camera Eye,” which at first glance appears to be a throwback to the more technically ambitious prog past, turns out to comprise two songs of nearly equal impact and subtly streamlined arrangements.

Moving Pictures 40’s Super Deluxe edition helps highlight this innovative new direction for Rush in several ways. First off, there’s the album itself: Taking the excellent 2015 remaster and putting it on both CD and 180-gram vinyl (cut at half-speed and direct-to-metal mastering for the audiophiles), this reissue also includes a new Dolby Atmos and 5.1 surround-sound mix on Blu-ray, a fantastic way to hear Alex Lifeson’s riffs pried apart from the synths and delivered as though the sound were enveloping you as you listen.

But it’s in the bonus vinyl and discs where Rush’s strengths at the time really shine. There are plenty of great live Rush records, but this previously unreleased concert, taken from Rush’s home base of Toronto concerts on March 24-25, 1981, is so razor-tight and remarkable, it’s genuinely surprising it’s taken this long for it to get an official release—though likely to do with the similar lightning-in-a-bottle magic of Exit…Stage Left, released only six months later and taped in part during the same tour. Each track rolls implacably forward, a band at the height of its powers, knowing it has just crafted something remarkable. (There’s a reason certain Rush live albums, like the pre-Presto release A Show Of Hands, don’t quite sizzle with the same intensity.)

But the argument for Moving Pictures’ centrality in the band’s catalogue isn’t just auditory. An accompanying 44-page hardcover includes encomiums from a variety of musicians, including Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil, Primus’ Les Calypool, and the late Taylor Hawkins, all of whom touch on the ways Rush has influenced subsequent generations of musicians in ways both overt and subtextual.

Thayil, in particular, explains how Moving Pictures represented a profound synthesis of genres that kept the band relevant in an era where disco, synth-pop, and other new genres were arising to supplant the old hard-rock vanguard of the ’70s. By building “a loyal fan base that had come to expect innovation and experimentation from the band, they could expand their sound… Rush was a band that was willing to take risks, grow and challenge themselves, allow[ing] them to succeed during this period of rapid transformation and expansion for rock and pop music.” Rush not only survived the shift, but thrived.

Of course, any special edition of a reissue needs to cater to the die-hards, and in this case, that means a very simple demographic: the Rush nerds. Accordingly, there’s a bevy of trinkets accompanying the Super Deluxe edition of Moving Pictures 40: A pair of signature Neil Peart drumsticks, metal guitar picks engraved with Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson’s signatures, a replica 1981 tour program (with pages of notes from Peart), a pair of posters, a 3D motion litho of the album cover, and more. (The nerdiest touch might be the Hot Wheels-sized Red Barchetta model car.) The complete list can be found here, but anyone who has gotten high and listened to Rush knows that looking over Peart’s hand-drawn lyrics pages (recreated here) while you listen is part of the experience.

Such accouterments can be seen as either enjoyably over-the-top collectibles or price-gouging nonsense meant to separate fans from yet more money; the truth is, like most things, it’s a bit of both. (Capitalism: It’s complicated!) But it seems undeniable that the 40th anniversary of Moving Pictures makes, if not the definitive case for the record’s pride of place in the Rush discography, then at least the most overwhelming one. Here was an album that demonstrated a hard rock band that could evolve and change colors with chameleonic efficiency, adapting to any environs in a manner that still allowed a fundamental musicianship unmistakably their own to shine through. And, in case revisiting these songs didn’t make it clear, once more: Holy hell, they kicked ass.